Athens - Vatousa

Athens - Vatousa

ATHENS: Monday July 30th

Making the transition from Kalotrelochoro to Athens lifestyle is not easy. When we arrive on Saturday evening the city is empty. Everyone had left early for their vacations. We find an air-conditioned taxi and I would be happy to ride around in it for the next three days. As it turns out that seems economically unfeasable so we go to Mary's house in the Plaka. I make a couple calls, leave a message with Corrine's machine and speak to Dorian's wife. Dorian is on his way out for a concert with Orchestra Mouraba, a sort of dance band for people in their fifties led by a sixty year old maestro. It is kind of a lame excuse. He could take a minute to speak to me but I know that he resents when I come back and disrupt his life. He's so content to wallow in his misery and it irritates him when I offer him solutions. Instead I walk down to the platia to buy a Herald Tribune and catch up on the world of Baseball. I have to walk all the way to Syntagma to find one because they are all out at the kiosk I usually get it f

rom.

There's another closer but the man and women who own it are so mean I refuse to buy anything from them. If I stop to gaze at the headlines they yell at me. If I decide to buy one and try to take it off the rack they tear it away from me and scream bloody murder. So I would rather walk a mile out of my way then give them what amounts to a dollar and a half. Seems pretty silly now that I think about it.

So I take my newspaper and sit at The Cafeneon, the well known old style ouzerie and my favorite hang-out, which is conveniently right next to Mary's apartment. I order a nice cold beer which is warm by the time it arrives, but I don't complain. I happily read my paper and wait for Andrea to show up, which she never does. I finally give up and start walking towards Mary's. Just as I get to her building the phone rings and Mary answers it. It's Corinne and Mary starts to tell her that I'm out but sees me pass by the window and hands me the phone in the street. Corinne says she and Patty are going to meet us at the Cafeneon at about eleven this evening.

We go out to dinner, or try to. Food-wise Plaka has become a wasteland as I mentioned earlier. There is good food to be found but all the nice little tavernas have become tourist rip-off joints. There are only two or three choices for the locals in the summer. In the winter it's better. The downstairs restaurants that specialize in bakalaro (fried cod-fish) are all open, but in the summer, with no air-conditioning it's pointless for them to serve food because you wouldn't be able to sit inside for more then five minutes. So as it turns out they are the only establishments that haven't sold out, only because they can't. The only time they can be open is in the winter when there are no tourists. It's too bad because I would have been there every night.

In the summer it's not so easy, in fact it's easier to lose friends when going out to eat in the Plaka. That's what happened to Andrea and I. It sort of begins the chain of anger that leads to our near breakup or what may very well turn out to be our breakup, though at the moment we seem to be talking again.

In the summer it's not so easy, in fact it's easier to lose friends when going out to eat in the Plaka. That's what happened to Andrea and I. It sort of begins the chain of anger that leads to our near breakup or what may very well turn out to be our breakup, though at the moment we seem to be talking again.

We were both in terrible moods, hungry, hot and in need of alcohol or caffeine and the first two places we go are so crowded that there is no chance of being served. My choice is "Psaras" my favorite restaurant in Athens. It's an old fish taverna but Nikos Mavriotis had told us that "Psaras is dead." The quality had gone down and the prices up. I'm still willing to take a gamble and not take his word for it, hoping from the depths of my heart that he is mistaken. Why would a restaurant that has been fantastic for the last hundred years choose this summer to become bad? It doesn't make sense to me. But Andrea is unwilling to take a chance. We have an argument and she gives in, but by then I don't want to risk being wrong so we go to the Cafeneon and order a couple ouzos and a tuna salad, not a very Greek meal. When Corinne and Patty came to join us Amarandi is becoming impossible and Andrea is also restless. They leave us and Corinne, Patty and I discuss life, relationships, and everything else under the sun u

ntil it's time for them to leave.

The next day we are walking down the newly pedestrionized Ermou street. I had been hinting about my apprehension about Mytilini ever since we'd arrived in Athens. I pushed Andrea to the boiling point.

"I am leaving you. I am sick of your psychological abuse. You don't want to come to Mytilini then don't. Get on a plane and go back to the states. But when we get back there I'm saving up my money and moving away from you and I am taking your daughter with me."

That sobers me up quickly. "Wow. She is right. I have been torturing her." I was proud of myself for never getting violent and here I was psychologically abusing her for the last two days. Maybe longer. It's a moment of profound realization and I swear to myself that I will be more aware. As far as I'm concerned, the war is over Of course I don't want to admit it to Andrea and lose face. Rather then announce a momentous turning point, I will go for the quiet change approach.

THEOPHOLOS

After a hectic trip through Athens and Pireaus, I am sitting in the first class lounge of this enormous ferry with Andrea, Mary and a sleeping Amarandi, who has missed all the excitement of getting on the boat with all our luggage. The ship is packed and as far as I can tell, not with tourists. I haven't seen one yet. When we arrived on board there were hordes of people lined up to get their cabins. Mary took the tickets from Andrea and pushed her way to the front calling out "Make way for a lady with a baby." We were given a cabin in two minutes. If it had been Andrea and I we would have waited on line for two hours. I'm impressed. I tell Andrea that she should go into business with Mary, a gem dealer, who travels by herself to India and buys precious stones to sell in Greece. Maybe some of Mary's take-charge attitude will rub off on Andrea.

Our first class cabin is more like a prison cell. It does have a shower though. As for the rest of the ship, it is too big to have any character. It's a former Scandinavian ferry, obviously newly purchased because they haven't removed the maps with it's route from Copenhagen to Leningrad. I go on deck to watch the overdue departure from Pireaus. There is an army of trucks and people waiting for other ferries to take them away from miserable sweltering Athens. One section is totally populated with backpackers from the USA and Northern Europe. They must be waiting for the ferry to Ios and Santorini which is working overtime trying to fill the islands to capacity.

We have to fight our way into the first class restaurant for dinner. It isn't worth it. As Mary points out, it's better to go to the self-service restaurant because at least there you can see what you are getting. Exactly my thinking. Anyway it's the same food. There's only one kitchen. After eating we go back to the cabin. I take the top bunk. No chance of any kind of sex action in these quarters. The cabin is the Scandinavian method of contraception, low ceilings, skinny bunk bed and itchy blankets.

LESVOS: August 1st

The porters bang on our door an hour away from Mytilini so they can clean the cabins before the passengers going back to Athens board even though the ship won't leave for another 12 hours. I take my time and shower, my first hot water since the Hotel Stavros in Sifnos. We take our bags upstairs where people are already packed in like sardines, so they can be among the first to exit when we dock. We go to the ship's bar and have a coffee while we look at the passing buildings on the outskirts of the city. Even after we have docked we wait around for the crowd to thin out. As we are about to load ourselves up to move towards the ramps, a man comes onto the ship asking if anyone needs help. We give him our backpacks and follow him as he sure-footedly makes his way through the lingering stragglers who are nearly impaled on my protruding speargun. He leaves our stuff on the dock and we pay him five hundred drachs, a bargain.

The porters bang on our door an hour away from Mytilini so they can clean the cabins before the passengers going back to Athens board even though the ship won't leave for another 12 hours. I take my time and shower, my first hot water since the Hotel Stavros in Sifnos. We take our bags upstairs where people are already packed in like sardines, so they can be among the first to exit when we dock. We go to the ship's bar and have a coffee while we look at the passing buildings on the outskirts of the city. Even after we have docked we wait around for the crowd to thin out. As we are about to load ourselves up to move towards the ramps, a man comes onto the ship asking if anyone needs help. We give him our backpacks and follow him as he sure-footedly makes his way through the lingering stragglers who are nearly impaled on my protruding speargun. He leaves our stuff on the dock and we pay him five hundred drachs, a bargain.

We walk along the main road on the waterfront and into Mary and Sophie's Rent-a-Car, now called Just Rent-a-Car. Sophie, our friend from two years ago, had moved to Plomari and is renting rooms. Her sister Mary is running the business now. She has one car left.

"You're gonna love it" she tells me as we walk to the yard to inspect it. She was right. It's a brand new Kid, by Peugeot, bright red with a cassette player, and best of all it has four doors.

We walk over to our favorite coffee shop across the street from our favorite yogurt shop and have a couple espressos. Then we take a stroll through the old market place. It's alive, full of people. Fish sellers are shouting their prices. I can't walk past a fish market without examining every crate of fish on display. Here in Mytilini it's mostly sardines, kolios (mackerel), some gopa, kefalo, barbouni and something called gavros which I think is anchovies. Everything is dirt cheap and fresh. Lesvos is the only island left that still has plenty of fish.

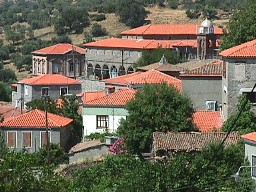

We go back to the car and are on the road by ten. We cross the big island past inland seas, great planes and high mounatins to our destination, the traditional villages of Xidera and Vatoussa.

VATOUSA: August 2nd

I am sitting in the old cafeneon with my back to the panoramic view of the lower village and the valley and mountains beyond. Inside are old men talking and playing cards. A few younger men are drinking ouzo, not bothering to pace themselves. As far as I have been able to tell the old guys don't begin drinking until noon, still fifteen minutes away. The crowd has thinned out in the last half an hour. It was packed with old men speaking loudly to be heard. Where they have all gone, I don't know, probably to the other cafeneon across the street. Perhaps there are other cafes scattered throughout the village. That's life here in the mountains of Lesvos. Moving from cafe to cafe all day drinking ouzo and Turkish coffee. (They still call it that here.) The younger old men work in the early morning. By noon it's too hot. The older men are retired and they hang out to leave their wives in peace, or to find peace themselves. This Cafeneon sits next to a huge platanos tree in a cobblestone platia where the tables and

chairs spill out onto. It looks like a perfect world for an old man. For the young it's a different story. There are a few children around but when they get older they will move away to the city of Mytilini, but more likely Athens. In that sense it is a dying village except there are people who are moving back for the simple life Vatousa has to offer. There is construction everywhere, all in the traditional style because this is a protected village.

I am sitting in the old cafeneon with my back to the panoramic view of the lower village and the valley and mountains beyond. Inside are old men talking and playing cards. A few younger men are drinking ouzo, not bothering to pace themselves. As far as I have been able to tell the old guys don't begin drinking until noon, still fifteen minutes away. The crowd has thinned out in the last half an hour. It was packed with old men speaking loudly to be heard. Where they have all gone, I don't know, probably to the other cafeneon across the street. Perhaps there are other cafes scattered throughout the village. That's life here in the mountains of Lesvos. Moving from cafe to cafe all day drinking ouzo and Turkish coffee. (They still call it that here.) The younger old men work in the early morning. By noon it's too hot. The older men are retired and they hang out to leave their wives in peace, or to find peace themselves. This Cafeneon sits next to a huge platanos tree in a cobblestone platia where the tables and

chairs spill out onto. It looks like a perfect world for an old man. For the young it's a different story. There are a few children around but when they get older they will move away to the city of Mytilini, but more likely Athens. In that sense it is a dying village except there are people who are moving back for the simple life Vatousa has to offer. There is construction everywhere, all in the traditional style because this is a protected village.

As far as I know, the village is known for two things. The first is the local orange and lemon sodas that are sold only within a ten kilometer radius of Vatousa. The other is because Andrea's sister lives here, or at least owns a house. That's the reason we are here today.

Pamela gave Andrea and Mary a list of twenty things that were to be done to the house. The idea that you can give instructions to Greek contractors, go away for two years and expect it to be done when you return is unrealistic. Of the twenty items on the list not one of them had been done, even though the house looked like a construction sight and was unlivable when we arrived. I had driven the small Peugeot up the tiny roads of the village lined with stone houses with inches to spare on each side only to find to my horror that I could go no further and had to back down the way I had come. It was difficult enough going foreword and by the time we had extricated ourselves from the cobblestone maze, I was ready for my first ouzo, or several. We headed for Xidera, the village of Andrea's totally insane grandmother, who had died several years ago in a trailer park in California. We were greeted with open arms by the old men of the village who I had photographed a few years ago and then sent duplicates to them. It

's possible that every home in the village has at least one of my photos stuck in a corner of a mirror.

Pamela gave Andrea and Mary a list of twenty things that were to be done to the house. The idea that you can give instructions to Greek contractors, go away for two years and expect it to be done when you return is unrealistic. Of the twenty items on the list not one of them had been done, even though the house looked like a construction sight and was unlivable when we arrived. I had driven the small Peugeot up the tiny roads of the village lined with stone houses with inches to spare on each side only to find to my horror that I could go no further and had to back down the way I had come. It was difficult enough going foreword and by the time we had extricated ourselves from the cobblestone maze, I was ready for my first ouzo, or several. We headed for Xidera, the village of Andrea's totally insane grandmother, who had died several years ago in a trailer park in California. We were greeted with open arms by the old men of the village who I had photographed a few years ago and then sent duplicates to them. It

's possible that every home in the village has at least one of my photos stuck in a corner of a mirror.

Within minutes of parking in the platia I was drinking an ouzo and eating meze with my friend Thanasis, who the villagers call The Australian because he had moved there for a few years before coming back, a decision he has been questioning ever since. It's an old man's society and Thanasis is my age saddled with a wife, two pre-teenage boys, a cafeneon and a herd of sheep and goats that he walks two hours over the mountains, to feed everyday, and then walks back. I tell him that I think he made the right decision even though it might not seem like it now.

"By the time you get to their age," I say motioning towards the old men lined up drinking ouzo in the cafeneon across the street, "you'll realize I was right. You just came early to get a good seat." Already his kids are drinking ouzo with lunch. Maybe it helps with their afternoon naps.

The village life revolves around ouzo, some home made, some the commercial Mytilini variety. All of it better then the stuff the big distillers export to America. All the men have a glassy-eyed opiated look. When a car or pickup truck slowly makes it's way past them on the narrow roads their eyes follow it into the distance and continue gazing until someone says something to break the spell. You can't say they are bored. Their minds are functioning in a different gear then ours. While some of the men play cards for hours, others look on for hours. My laptop attracts an interest but only a passing one. They are more at home with the familiar. In other places a stranger may be questioned endlessly about life in America. Here they could give a damn.

The conversation is more like "How's it going? The baby's grown. Ahhh...nice breeze." They can sit forever without feeling the pressure to fill up the empty space by saying something. The old men come and go appearing at different cafeneons in various formations all day long. There are just under four-hundred inhabitants in Xidera, perhaps a third of them men. There are seven cafeneons. The women don't go there. They stay within the walls of their homes and gardens until sunset when they come out to sit in groups on the street and gossip.

The conversation is more like "How's it going? The baby's grown. Ahhh...nice breeze." They can sit forever without feeling the pressure to fill up the empty space by saying something. The old men come and go appearing at different cafeneons in various formations all day long. There are just under four-hundred inhabitants in Xidera, perhaps a third of them men. There are seven cafeneons. The women don't go there. They stay within the walls of their homes and gardens until sunset when they come out to sit in groups on the street and gossip.

Our mission is simple. Make sure the work was done checking off the items one by one, then take photos and speak to the individual contractors in case there are any problems. We would either sleep in Pamela's Vatousa house, impossible since it was now a construction site, or in Andrea's grandmother's house in Xidera which we discover, is worse. The window frames and ledges had all been replaced but the rest of the house is falling down. The floor is covered with debris. We attempt to make it livable but give up when we realize it would never be safe for Amarandi. While the girls discuss our options I walk to the platia and sit with the village drunken priest and look at the map. Gavatha seems like the best and closest place so we pile into the car and drive off.

GAVATHA

Gavatha is a tiny fishing port at the end of a lush plain between several mountains. There is nowhere to stay in the village itself and Mary is beginning to lose her composure. We send her into a hotel to get information and she comes out in a frustrated panic because there is only one available room which means she will have to "share her space" with us. This idea horrifies her. It puzzles me because Andrea and I have been on our best behavior. We haven't had one argument or extended period of bickering. Mary is just having trouble dealing with the normal setbacks and tribulations of Greek island group travel. As far as I'm concerned once we rented the car, everything was fine. I don't care where we stay. I'd just as soon drive twenty-four hours a day, taking little catnaps when I can.

Gavatha is a tiny fishing port at the end of a lush plain between several mountains. There is nowhere to stay in the village itself and Mary is beginning to lose her composure. We send her into a hotel to get information and she comes out in a frustrated panic because there is only one available room which means she will have to "share her space" with us. This idea horrifies her. It puzzles me because Andrea and I have been on our best behavior. We haven't had one argument or extended period of bickering. Mary is just having trouble dealing with the normal setbacks and tribulations of Greek island group travel. As far as I'm concerned once we rented the car, everything was fine. I don't care where we stay. I'd just as soon drive twenty-four hours a day, taking little catnaps when I can.

But Mary, with our first failed attempt at finding a room has given in to despair. We try several other places but none are suitable. While the girls are ready to move on to Sigri, forty-five minutes away, I want to check the other side of the valley where all the farms are. We drive through the winding dirt roads and find two remote tavernas right next to each other. At the first one a young man who's name is Kosta, directs us to a shack, at the end of a paved over riverbed that is serving as a road in the dry season. It is owned by an old man named Apostolis who has given up on his attempt to run a beachside ouzerie because there are no customers. He has two rooms next to his house. He charges five thousand for the pair and we take them.

The rooms are in a cinder block shack in the middle of his garden. I can see and hear the sea from the small front porch. There is a river nearby, or what is probably a river in the rainy season. In the summer it is several small pools full of frogs and if our landlord is telling us the truth, eels, which people come to catch and eat.

The rooms are in a cinder block shack in the middle of his garden. I can see and hear the sea from the small front porch. There is a river nearby, or what is probably a river in the rainy season. In the summer it is several small pools full of frogs and if our landlord is telling us the truth, eels, which people come to catch and eat.

"The frogs", he says, "keep the mosquito population down." This may be true. I haven't been bitten yet. Apostoli wants to sell the ouzerie for about twenty-five thousand dollars. His kids hate it here and are angry that he opened the place. They never visit. He gives me the lowdown and the grand tour of the property hoping I'll buy it. Maybe we'll get it for Andrea's mom.

The best thing about this place they call Campo, which means valley, is the taverna where we got directions. We go there to have an ouzo and to wait for a call from Pamela in New York. We end up staying there all night eating these incredible fresh sardines that are grilled, then served with lemon and oil. As we eat, the restaurant begins to fill up with Greek Americans and Canadians who are back for the summer. I speak with three teenage girls from Toronto and Vancouver who are on their way to the village of Antissa, fifteen kilometers away, where there are two bars. For the young people that is the extent of the night life in the area. I'm surprised there is any nightlife at all for them. The tavernas here were a surprise to me and the fact that this one was so good is a gift from God. I feel like we have stumbled upon another wonderful place and with the flexibility the car gives us I'll be happy to stay here if not indefinitely, at least another night. Andrea is not so enamored with Campo Antissa, and Mar

y merely tolerates it because she has made up her mind to leave by Friday, which is tomorrow. As long as she has enough of her terrible Greek pot, she can survive. She mixes it with tobacco, I suppose to conserve it. I have shared a few joints with her and it gets you stoned but it's so harsh on the throat it's almost not worth it. Plus, the ouzo obliterates the marijuana high in a very unsubtle way.

Being with Andrea and Mary is like experiencing an encounter group. It's interesting that they call themselves friends. If they are, the relationship is strained to the breaking point. They don't really converse, they more or less complain to each other about the disasters their lives have become. Now being here together is becoming another one of life's disasters. It has much to do with the pressure of dealing with Pamela's house business. They both obviously resent having to do it but they don't have the courage or strength to say no because Pamela has such a forceful personality. Yesterday at lunch they were on the phone with her for an hour in Andrea's aunts cafeneon in Xidera. At least five times they were cut off and each time Pam called back, asking questions, giving instructions and counter-instructions. She wanted Andrea to go to the carpenter and threaten him that he was not going to be paid and tell him that he was going to pick up the tab for our hotel room. The pressure is building because the mo

re they say yes and agree to do Pamela's bidding the more they take it out on each other.

August 3rd

Today we wake up ten minutes before we are supposed to meet the builder at Pam's house. We quickly get dressed, drive to Vatoussa and park in the square. If it was me I would go to the house first. Mary decides to have breakfast even though she is almost an hour late. Then instead of going directly to Pam's house where the guy might possibly be waiting for her, she goes to check out the other construction sites in the village because she thinks he is probably there. I stay out of the equation. I'm supposed to keep Amarandi with me but I know that as soon as Andrea gets out of sight she will start screaming for her mother. When Andrea walks up the hill Amarandi follows her and I go into the cafeneon to write. They are done in less then an hour and we get into the car and drove to Xidera for lunch and an hour of transatlantic construction instructions from Pam.

Today we wake up ten minutes before we are supposed to meet the builder at Pam's house. We quickly get dressed, drive to Vatoussa and park in the square. If it was me I would go to the house first. Mary decides to have breakfast even though she is almost an hour late. Then instead of going directly to Pam's house where the guy might possibly be waiting for her, she goes to check out the other construction sites in the village because she thinks he is probably there. I stay out of the equation. I'm supposed to keep Amarandi with me but I know that as soon as Andrea gets out of sight she will start screaming for her mother. When Andrea walks up the hill Amarandi follows her and I go into the cafeneon to write. They are done in less then an hour and we get into the car and drove to Xidera for lunch and an hour of transatlantic construction instructions from Pam.

After we eat and Amarandi and I walk around the village we drive to Sigri, a fishing village on the northwest tip of the island. It's like Batsi in Andros. There are Greek-Americans and British package tourists in a disorganized town that has been reincarnated into a holiday village. There is a Greek destroyer tied to the dock to give the tourists that pleasant living in the war-zone feeling. There is a medieval castle that used to guard the town but is now used as a place to dump garbage. There is a black oily substance on the rocks in the harbor. There is a long island that shelters the bay and even though there is not a house in sight it's covered with telephone or electric utility poles. It looks like a pleasant place to visit if you don't mind falling into a missile silo. Still the tourists happily paddle around in their little boats or lay on the beach turning their tender white British skin into seared red flesh.

Mary hates the tourists. "Why don't they go away and let the people go back to the farms?" It's too late. If they go away the people will go back to starving. They gave up their gardens and fields to build rooms to rent. The whole society is built on tourist dollars. What else does Greece have to offer the rest of the world? Their biggest export is cement. They slowly chip away at their sacred land and send it in bags and cargo ships to the rest of the world. Andrea takes great offense at Mary's scorn for the travelers.

"Don't worry Mary," she tells her. "Soon they'll all be gone. They'll take their money where it is worth something. They'll go to a country where they are not resented and looked down on and you'll have your beautiful country back. Only by then you'll have completely destroyed it and nobody in their right minds will want to visit." I can't tell if she really feels that way or she is just sick of Mary. At this point of the trip I don't care.

"Don't worry Mary," she tells her. "Soon they'll all be gone. They'll take their money where it is worth something. They'll go to a country where they are not resented and looked down on and you'll have your beautiful country back. Only by then you'll have completely destroyed it and nobody in their right minds will want to visit." I can't tell if she really feels that way or she is just sick of Mary. At this point of the trip I don't care.

They want to sit in a traditional cafeneon. Amarandi is asleep in the car and I tell them if we can't find a shady spot close by, I'll park under a tree down the road and wait with her until she wakes up. I really don't mind. I have grown very close to the car. Mary interprets this as me being difficult and says she is going to leave and take a taxi. I ask her where.

"Anywhere!" she snaps.

It didn't matter because we find a parking spot right next to the cafe. Mary orders a candied baby eggplant, a dish I had never seen and am reluctant to try. It's good. Well, anything is good cooked in that much sugar. You could eat candied cigarette butts if you cooked them long enough. Just as she is starting to enjoy it a lone wasp takes interest and she has to abandon it to the next table. It's that kind of day for Mary, maybe that kind of life. I walk off and buy a USA Today. Damn. The Mets have traded Brett Saberhagen.

August 4th

We wake up on Friday too late for Mary to catch the bus to Mytilini so she can get her boat back to Athens. Actually we wake up in plenty of time but Mary futzed around for a couple hours so she wouldn't have to take the bus and we would have to drive her. I want to get our brakes checked out too, they are making a lot of noise. We lost our hubcap somewhere too. Then yesterday as we were driving through the tiny village of Revma next to Xidera, Mary yelled for me to stop the car.

"Look at the flowers!" she shouted from the back seat. I didn't know what she was talking about. What's so great about the flowers? Then I saw, nailed to a tree above a flower box was our hubcap. We happily thanked the man who owned the nearby cafeneon who told us that tree was the lost and found for the village. I tried to put it on but it didn't fit. Perhaps it wasn't ours, but who cared. It said Peugeot. What more did we want? There was an old guy waiting at the cafe in need of a lift to Xidera. He turned out to be the old man we had run into at a fast food joint in Mytilini who had helped us carry our bags to the ship three years ago during that painful episode of my first visit to the island. He remembered us and we all became very excited.

We drive to Mytilini and drop the car off at the rental office. There was some dust on the brake-pads and it only takes a few minutes to fix. We walk with Mary to the cafeneon next to the ferry dock and she and Andrea have one final discussion about Pamela and her house. They decide that they have done a valuable service to her. Pamela had sent detailed plans that she had painstakingly drawn up. They were very concise and readable to any professional architect. The trouble was she had given them to a village house builder. She might as well have given him instructions in Japanese. The pictures she had drawn were impressive, with many different views, but the builder had shrugged his shoulders and started to do what he wanted to do. If we hadn't come to stop him, Pamela, who had bought the house because it was in a traditional village, would have the most un-traditional home there. She would have taken one look at her house and been so horrified that she would have to tear everything down and start over. Andre

a and Mary had saved her about twenty thousand dollars.

We drive to Mytilini and drop the car off at the rental office. There was some dust on the brake-pads and it only takes a few minutes to fix. We walk with Mary to the cafeneon next to the ferry dock and she and Andrea have one final discussion about Pamela and her house. They decide that they have done a valuable service to her. Pamela had sent detailed plans that she had painstakingly drawn up. They were very concise and readable to any professional architect. The trouble was she had given them to a village house builder. She might as well have given him instructions in Japanese. The pictures she had drawn were impressive, with many different views, but the builder had shrugged his shoulders and started to do what he wanted to do. If we hadn't come to stop him, Pamela, who had bought the house because it was in a traditional village, would have the most un-traditional home there. She would have taken one look at her house and been so horrified that she would have to tear everything down and start over. Andre

a and Mary had saved her about twenty thousand dollars.

Having decided this, they run to put Mary's stuff on the boat which had begun to untie its ropes in preparation for leaving. We stand on the dock waving as the SAPHO pulls away and sails out of the harbor, followed by a destroyer escort to protect it from a Turkish sneak attack.